Attracting international scientists should be used to complement a domestic science base, not compensate for its deficiencies.

It was the coronavirus pandemic that first showed the importance of maintaining a robust (and diverse) internal supply chain to respond effectively to external stressors. Before, in the boom years of globalisation, outsourcing medical supplies (manufacture of medical masks, drugs, gowns) had been a way of maximising efficiency and minimising cost. Until the supply stopped.

Russia’s attack on Ukraine provided the same lesson for energy. Europe had been guzzling Russian oil and gas like a drunk in a saloon, only to suddenly find that the hitherto generous provider was turning the taps off. It showed that single sources create systemic weaknesses, and a diversified portfolio is necessary to create resilience to shocks and reduce the risk of unreliability (or even blackmail) on the part of the supplier.

Of course, the concept of a diversified portfolio is nothing new, going back at least as far as Alfred W. Jones’s original conception of a hedge fund – or, more properly, a “hedged” fund in which the portfolio owner literally hedges their bets, buying some stocks that they think will increase in value and shorting others that they think will decrease in value.

And what applies to finance, as well as energy and medicine, also applies to science.

Science is one of the very few genuinely international careers out there, with movement between countries viewed positively and the skills required to flourish in any one location being shared almost completely with any other location.

America was the original scientific talent magnet, so much so that the “brain drain” heading across the Atlantic was a constant lament until recently, but nowadays most wealthy countries and institutions are vying to make themselves attractive to researchers from all around the globe.

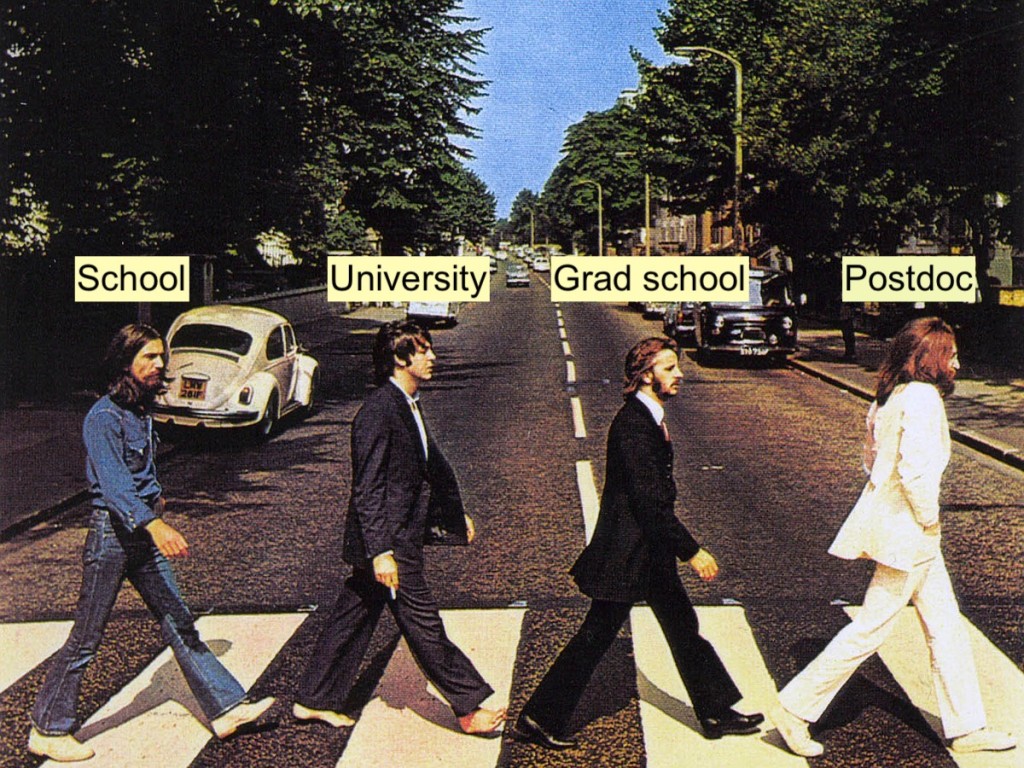

Research may be the glittering crown, but the body and foundation below it is undergraduate and postgraduate education and training. Underpinning them in turn is school education and training.

My school and undergraduate years taught me about science and the scientific method. At Master’s and postgraduate level I learned to apply the scientific method to generate new knowledge. During my postdoc I refined my own style of doing so, and as a group leader I began to directly transmit that philosophy.

Every step was contingent on the one before it. I benefitted enormously from opportunities to excel (winning a scholarship to a private school and later winning admission to an elite international university), things which are not available to many, but are less critical in a more egalitarian educational system than the one present in the U.K.

That supply chain cannot be allowed to rust. Education and training cannot be outsourced wholesale.

Yet we’ve outsourced schooling and undergraduate training when we recruit international PhD candidates. We’ve outsourced postgraduate education when we recruit international postdocs. And we’ve outsourced the entire supply chain when we recruit international group leaders.

To be sure, recruitment of international scientists at all career stages is a good thing. It helps diversify the environment, enriches the science base through the import of different philosophies and skills, and can also buffer the academic sector against short term fluctuations in supply.

But it cannot supplant a domestic system. When UK universities are taking fewer domestic students because they need the extra income from international students to balance the books, this should be a red flag. When universities almost wholly delegate the responsibility for funding PhD students to group leaders and their grants, this should be a red flag. And when research leaders are criticised for not hiring more domestic scientists but in fact the domestic candidates are simply not the same calibre as the international applicants, that should be a red flag.

Complete reliance on a single source, be it domestic or international, cannot be good for the system. Over-reliance on domestic sources will limit innovation; over-reliance on international sources will encourage neglect of domestic production. Both scenarios are fraught with risk that the supply could dry up. And in the febrile current political climate, when hostility to immigration is a vote-winner throughout Western countries, an unavoidable consequence is that this attitude will make international scientists less likely to arrive, and less likely to stay. Scientific supply chains have to be sustained, and protected.

Dear Brooke,

a wonderful analysis directly to the point. The neglect of teaching students of your own University – because you harvest the “top” scientists on the international market – results in less competitive science in the long run.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Andreas, many thanks for taking the time to write, much appreciated. As usual, we seem to be philosophically aligned on this issue. 🙂

LikeLike