I’m less than a year into my new scientific career in the private sector, and the biggest difference with academia is already clear: it’s the money.

But not, as you might think, in terms of salary…

…instead, it’s the amount of money in the system as a whole. What is noticeable, what is tangible, what is inescapable in every client interaction, every project, every news item that comes along is how much capital there is sloshing around in the biotech/pharma sector.

Sure, firms may run out of cash and there’s a general recognition too that the last 6-9 months have been among the toughest in recent memory. Even the most successful companies may have to tighten their belts from time to time, agencies who depend on their clients’ largesse will lose work if the market takes a downturn, and organisations do routinely go under, but nobody questions or doubts that funds and opportunity abound in the industry as a whole. If the money dries up in one place, there’s guaranteed to be a new source that can be tapped elsewhere.

Consequently, there’s a prevailing mood of either cautious or overt ebullience, in part because the necessity and the relevance of what the sector is doing is a given. The size fluctuates, companies are born or go bust, but the edifice itself remains enormously large, both valued and valuable, and with the finances to back that up.

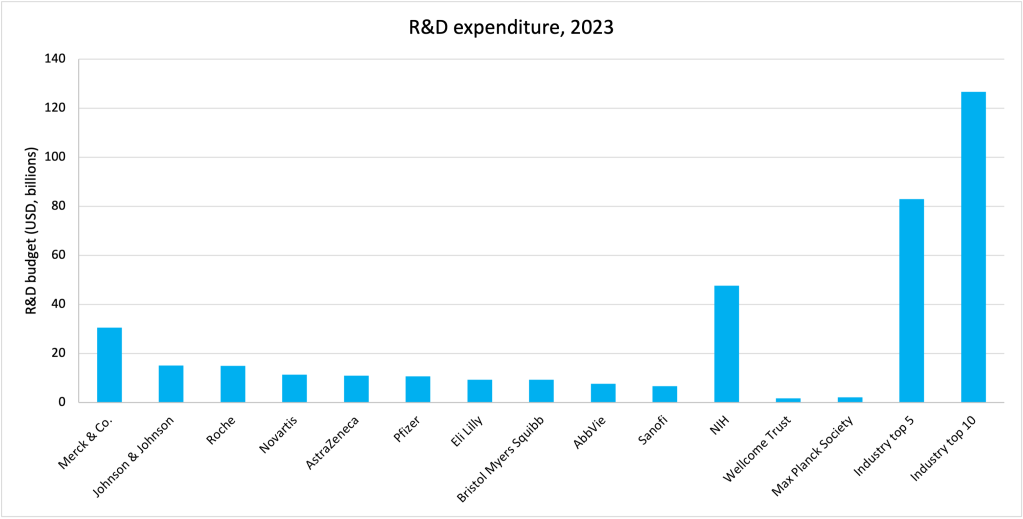

How big? Well, take a look at these numbers, because the difference is there not just in relative or in psychological terms, but absolute ones as well. Below are the top 10 biotech/pharma Research & Development (R&D) budgets for 2022. The top 5 combined add up to nearly $20 billion more than the budget for the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which is the main public funder of biomedical research in the USA. The top 10 combined are more than double the NIH budget.

Think that’s an aberration? Not at all – here’s the same set of data for 2023. The trends hold.

Remember that these are single (albeit massive) companies, but these single companies are each stumping up more money for R&D on an annual basis than the Wellcome Trust and the Max Planck society – two of the biggest academic research funders in the UK and Germany – COMBINED. And these are merely the ten largest representatives of an entire industry. This is how vast the biotech/pharma sector is.

Psychologically, the contrast with academia could hardly be greater. There’s obviously a decent amount of public money committed to academic research, but not enough to everybody, and so the 21st century scientist-academic’s life is spent in a constant, panicked pursuit of funds simply to keep things going.

The bald truth is that large areas of the academic system prop themselves up by chronically undervaluing their workforce, extracting enormous amounts of unpaid and unrecuperated overtime, and cynically leveraging the vocational commitment of their employees, all to compensate for a perpetual shortage of cash.

The outcome is that regardless of how much money there might be in the system, there never seems to be enough. That in turn creates a pervasive sense of unease and a prevailing sensation of scarcity, driven not least by the lack of permanent positions (known in other sectors simply as “jobs”)…I still remember arriving as a postdoc at Yale and being astonished that there, in that most prestigious and privileged of places, the overriding emotion was fear. Fear that grants wouldn’t be renewed, fear that work would be scooped, fear of failure.

What the funding disparity between the private and public sectors also suggests is that in the private sector people are being paid appropriately for their time. If you want smart, highly-trained and specialised workers then you need to be able to pay for them (and pay them for every hour worked), and that costs a lot. Might the size of the biotech/pharma R&D sector therefore provide a more appropriate estimation of scientists’ and physicians’ worth?

As I’ve noted before and will always believe, academia can be great. If you are blessed enough to have career security, steady funding, stimulating research, enthusiastic students, and a reasonable administrative load then you really are living the dream. For many though – and, I suspect, for many of those not lucky enough to be born at a time of plentiful faculty openings – the wished-for life of scholarship gets compressed into a terrible, grinding slog to survive, with increasingly little pleasure to be had and only the panting relief of continued survival.

In such circumstances, we masochistically tend to laud our determination, our stoicism, our steadfastness in staying put in academia no matter how put-upon we are. But I would urge all of you who find yourselves in such a situation, to carefully assess your predicament, and consider following the money.

Acknowledgements

I’m grateful to Richard Sever (@cshperspectives), one of whose tweets first drew my attention to the remarkable size of pharma R&D budgets and which highlighted the top5 > NIH disparity.

Original artwork generated by Midjourney.

Sources

Biotech/pharma R&D budgets: 2022, 2023

Wellcome Trust funding: 2022, 2023

Max Planck society funding: 2022, 2023

Good points and while money is not the only difference, academics tend to compensate for the difference based on academic freedom, which is, to put it lightly, isn’t what it used to be. The bottom line is that the current size of academic science in most countries is too large for the funds that supply it. This problem has finally has come to the point of obviousness that funders are increasing minimum stipends on fellowships (at last). The penny has yet to drop as the large majority of trainees are funded from grants that have not received meaningful increases in 15 years or more – we’ve just carried on and passed off the fiscal pain in other ways. Of course, soft-money institutions will notice when less students (especially) and fellows are recruited as they are a significant revenue source. But it remains to be seen whether they will respond with more pressure or, perhaps, bite the bullet and be part of the solution (I’m not holding my breath).

BTW, Isn’t original art by Midjourney and oxymoron?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Jim, thanks for writing! I completely agree with your sketch…it’s very unfortunate that so many young (and not-so-young) scientists are caught up in the middle of this.

I do think it’s important that we train as many PhDs as possible, but I’m becoming more and more concerned at the way that so many are then encouraged to hang around in academia for years despite the lack of opportunities. The ways out need to be signposted. As suggested here, the biotech/pharma sector has no shortage of funds or capacity.

LikeLike

This is very informative, but I do think it is worth remembering that the majority of the R&D budgets at Pharma companies is on the D part, not the R part. So it isn’t quite an apples to apples comparision.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi David, many thanks for writing. That is a really good point, and absolutely worth bearing in mind. It would be fascinating to see a more granular analysis of the allocations from both private and public sources, but that’s something I’m not remotely qualified to do.

LikeLike