Did you know that there are actually guidelines for determining authorship on scientific papers?

Scientific authorships have an outsized impact nowadays on academic career progression, and consequently it’s no surprise that authorship status on publications can trigger all kinds of disputes and disagreements. In the medical sciences, the International committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) has actually codified a set of criteria for manuscript authorship, and although they’re primarily intended for medical research, the guidelines are good recommendations for other sciences to follow. They’re a simple set of conditions that are easy to understand but still allow plenty of space for interpretation.

Who IS an author

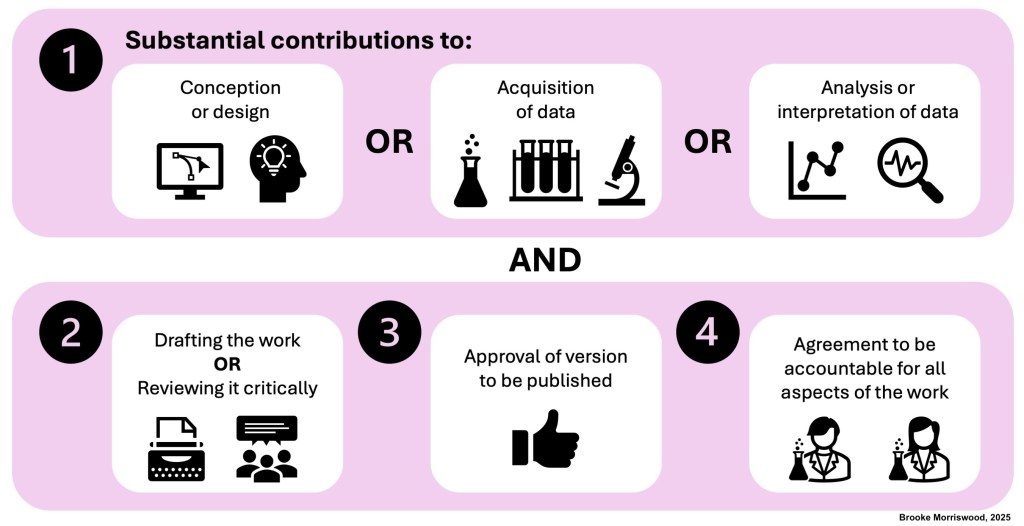

The ICMJE guidelines follow a simple 4-point system. For someone to qualify for authorship, they must fulfil all 4 criteria.

1. Substantial contributions to EITHER conception or design of the research OR the acquisition of data OR the analysis and interpretation of the data.

2. Drafting the work OR reviewing it critically.

3. Approving the manuscript for submission.

4. Agreeing to take responsibility (be accountable for) all aspects of the work.

Note that a key feature of these criteria is that authors have to be involved with the manuscript, and not just the experimental work – they cannot do experiments and then expect to sit out the manuscript preparation and still be credited with authorship. Conversely, scientists cannot simply be involved with the manuscript only; they have to have been involved with either the conception, acquisition, or analysis of the data. Approval for submission is also key: if your name appears on a paper then you MUST have approved its submission.

Who ISN’T an author

This is even simpler – anyone who does not fulfil all 4 points of the above system isn’t entitled to authorship. People who are involved in one, two, or even three of the points but not all four should therefore be listed in the Acknowledgements but do not qualify to appear on the authors byline.

Note that this also means that acquisition of funding, general administration, and editing or proofreading and other writing support don’t qualify as grounds for authorship. It’s also why people who have assisted only with the manuscript are fully entitled to a mention in the Acknowledgements but do not qualify for authorship.

Many shades of grey

While the criteria might initially seem quite proscriptive, they’re actually very inclusive. Importantly, the ICMJE explicitly says that anyone who fulfils criterion 1 (conception or design, or acquisition of data, or analysis) must have the opportunity to participate in preparation of the manuscript (criteria 2-4) if they wish. Denying such people the chance to be involved with the manuscript and then using that as grounds to exclude them from authorship is an abuse. This is a really important point because it explicitly endorses the notion that anybody who generated a substantial quantity of data for a paper is entitled to full authorship.

Exactly what constitutes a “substantial contribution” is vague however, and very much down to an individual’s subjective judgement as to whether they feel their involvement meets a threshold for inclusion. A scientist is always entitled to waive authorship, and some people may decline an offered authorship while others might demand it for exactly the same contribution. What constitutes “critical review” of a manuscript is similarly open – in theory, it is enough for an author to write “I have read and reviewed this manuscript and have no further comments” after a manuscript has been circulated for feedback.

Not being involved with the experimental work (the data acquisition) is no bar to authorship so long as that person has participated in either the design of the experiments or the analysis of the data (or both). Again, this is easy to reconcile with current practice as it describes the role often played by group leaders.

Ghosts and guests

Ghost authors are people who should be an author, but aren’t; guest authors are people who shouldn’t be an author, but are.

Ghosts can genuinely haunt a paper when researchers (often early-career researchers) are denied an authorship that they are entitled to. Ironically, the involvement of professional writers in the preparation of a scientific paper does not make them a ghost, because they don’t normally fulfil criterion 1; the same principle explains why generative AI can be used to assist manuscript preparation but should not be credited with authorship.

Guest authorships have historically been a problem in certain academic cultures and there can still be a strong sense of entitlement from some senior academics – remember again that a scientist who has not been involved in the design of experiments, acquisition of data, or analysis of the results is NOT entitled to authorship by ICMJE criteria; simply “running the lab” or “acquiring the funds” are not grounds for authorship and any scientist credited under such conditions is a guest.

The unsung heroes

There are two demographics in scientific research that are chronically underrepresented when it comes to authorships: technicians and Bachelor/Master’s students. As already noted, the ICMJE guidelines are actually very clear – ANYBODY who has made a substantial contribution to the design or acquisition or interpretation of data is entitled to an authorship if they want one, and should be included in the manuscript preparation as a result.

To all the techs and students reading this: don’t be alarmed at the notion of “reviewing”, “approving” or “being accountable”! As noted above, “reviewing” fundamentally means ensuring that there’s nothing in the manuscript you object you, “submission” merely means agreeing to submission to a journal, and “being accountable” is something that as a good scientist you always should be. You take responsibility for the quality of your own data.

To all the group leaders reading this: make sure you extend the offer of authorship to your technicians and students!

Corresponding authors

The corresponding author is usually but not always the senior author on a manuscript. The corresponding author is the main point of contact between the author group and the journal during the submission, review, revision, and post-acceptance process. The corresponding author is also, in theory, the main contact point for other scientists who wish to correspond with the author group after the paper is published.

It’s worth noting that both of these functions have become rather ceremonial. Senior authors who are corresponding authors often delegate the drudgework of manuscript submission to the first author or another subordinate, and writing a message to the corresponding author to discuss a published manuscript has – regrettably – become rather rare.

More progressive group leaders (and ones who genuinely feel that they are not the right person to respond to any scientific queries relating to the paper) may award corresponding author status to one of the early-career researchers in the author group, typically a postdoc or late-stage PhD who has demonstrated independence during the project process and who is actually best-placed to respond to any scientific enquiries about the research.

Last author, last word; first author, first heard

The last author is the senior author on a manuscript and bears ultimate responsibility for it. They will usually have overseen the project, helped design the experiments and interpret the data, coordinated with any collaborators, and arranged payment of publication fees. They also bear responsibility for ensuring that the manuscript contains sound data, and will be expected to resolve any disputes over authorship that arise.

The first author is traditionally the person who has generated the majority of the manuscript’s data, and who has usually also played an integral part in the project’s progression in terms of design and analysis. In academic publications, last author and first author are the two most prestigious positions on the manuscript’s author list, and consequently the most contested.

Sharing the glory

Any authorship position on an author list (first, second, third, last) can be shared if two (or more) individuals deserve equal acknowledgement for their contributions to the story. Note that a co-first authorship still counts as a first authorship even if yours is the second name on the list of co-firsts – don’t forget to note this in any publication lists on your CV.

Giving CRediT

The pre-eminence of first author and last author status can be very damaging, particularly to early-career researchers. It is common to hear of any authorship that is neither first nor last being dismissed as inconsequential, precisely because it is hard to measure the exact contribution made. The CRediT (Contributor Role Taxonomy) scheme addresses this shortcoming by providing a more granular means of assessing the contributions made by individual authors on the manuscript. It’s a 14-point list that ranges from “conceptualisation” to “writing – editing and reviewing” and an increasing number of journals require authors to list their contributions in this way. Or maybe we should award credit in a manner similar to films?

Further reading

If you’re interested in further reading on the topic, the most recent set of Good Publication Practice guidelines can be found here. These were developed for the publication of company-sponsored biomedical research, but comprise a set of rules that academic research would benefit by following.

Hope that helps! Any questions or comments, write below…

2 thoughts on “Credit where credit’s due (a short guide to authorships in scientific papers)”