Is knowledge really the primary product of academic research?

I am more than ever convinced that the most important output of research – relative to the level of societal investment – is the production of scientists.

From the outside, academic research looks like a fantastically wasteful activity. Literally millions of dollars of taxpayer money are invested in wringing secrets out of the natural world and developing new techniques, but a lot of the data generated using that money never gets published.

Some of it will not be publication-grade, some of it (“orphan observations”) is good but doesn’t find its way into a research publication, some of it ends up being replaced as a paper is revised, and some of it ends up sitting on the shelf, unpublished, for too long and becomes outdated.

Even high-quality data doesn’t guarantee a long half-life after publication. Individual papers, even highly influential ones, make a minimal impact by themselves, and the vast majority of scientific papers are not highly influential or even true breakthroughs, no matter what the hype merchants claim. It’s rare for a paper to be read or cited much after 5-10 years, and less in areas of high activity.

Faced with these kinds of outcomes, it’s perhaps natural that the public (and their political leaders) should be sceptical about whether this constitutes good value for societal investment, and perhaps explains why researchers will tie themselves in knots trying to explain the disease or health relevance of their research.

Because there’s a reason why “impact” sections of grants are so difficult to write and feel like a charade – deep down, we know that fundamental research is about generating knowledge, and that’s what we care about. That’s the impact. But there’s always an unease about saying that quite so nakedly. Forecasting impact is easy for applied research (possibly explaining its popularity with politicians) because it addresses an unmet societal need; fundamental research only addresses our need to learn more. It provides the raw material for innovation.

Every researcher is additionally affected by cognitive bias, because we all think that what we’re working on is one of the most interesting things out there, even though our nearest colleagues will probably disagree (because they naturally think that what they’re working on instead is one of the most interesting things out there).

So we tire ourselves out producing papers, but are continually rebuffed at the peer review stage – no matter how good it is, no matter how interesting we think it is, there will always be somebody (and often, many people) who simply don’t see it the same way.

This intense focus on our tiny little patch of research turf to the exclusion of much else (how many scientists are knowledgeable about specialisations outside their own?) warps and distorts our sense of perspective, as happens if we stare at something too closely for too long – we see the beauty of a single leaf, the intricate architecture of an ant, the sequestered secrets of the nucleus….yet that obsessive (and sometimes embittered) focus on the object of our research makes it easy to miss the people bringing it to light.

And perhaps that’s how it feels once you fully leave the bench behind, when you no longer do research with your own hands – like one of those scenes in a movie when someone sits still, fascinated at an object in front of them, while around them everything whirls and blurs in fast-forward. How fast ten years can pass on a research topic! How many people can pass through the doors of a lab, make their contributions to the object of fascination, and then leave almost unremembered.

This probably explains some of the extractive and exploitative practices in research. If the research is perceived as the most important thing, and the people doing it almost bystanders, then it becomes easier to appreciate why papers can get delayed for years even after students/postdocs – with a dragging handicap on their CVs – have moved on, why young scientists can be treated as disposable resources in pursuit of a longer-term aim, and why their struggles and problems can be received with unempathetic disinterest.

But there’s another way of looking at this system, and one which makes almost every cent expended look like a good investment – the human side.

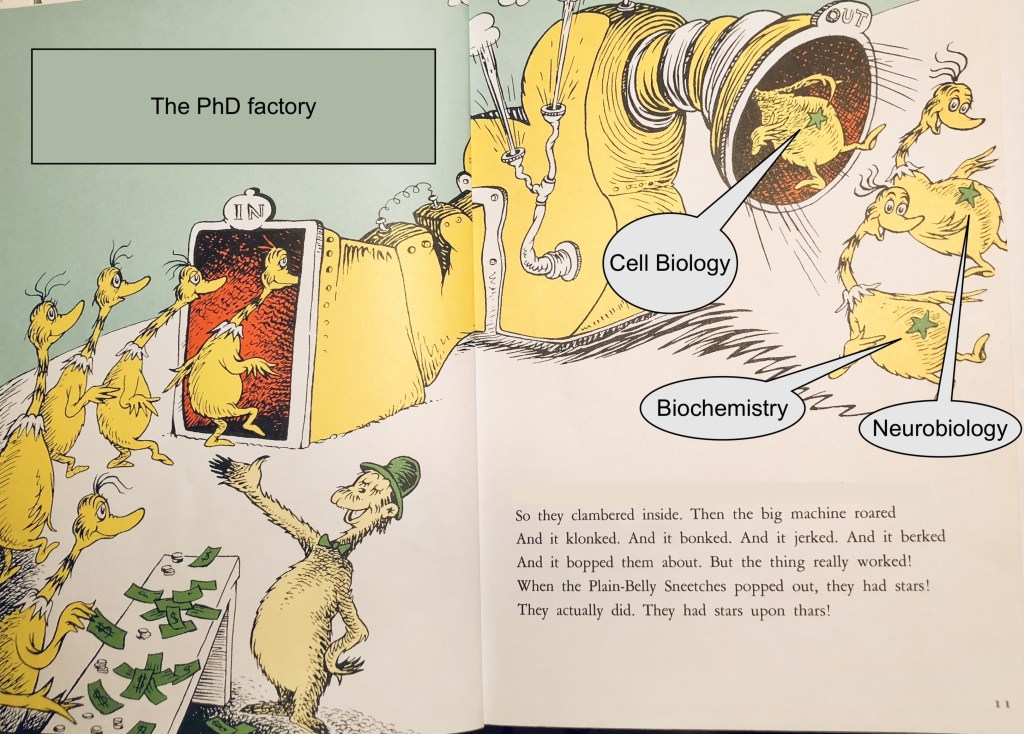

Because academic research doesn’t just produce science, it also produces scientists. And it is the scientists that are produced which represents the most tangible return on the level of societal investment. That is, undeniably, impact – the money is invested, and scientists are produced. Society ensures the production of more scientists.

Seen from this perspective, it is actually the papers – not the people – that are the (fascinating) by-product of this activity, and the quality of the papers produced partly reports on the quality of the training.

As a corollary, it is therefore important that those people, those scientists, can go out into the wider world with a positive sense of mission. They are the products of a significant societal investment, now equipped with the analytical tools to tackle real-world problems in a variety of spheres.

Scientists are needed more than ever in the industrial sector, in politics, in policy, in almost every facet of this increasingly data-driven world we live in. But the exceptionally research-orientated view of scientific output insists that these people are less important, and will never be more important, and should not be treated as more important than the projects they work on during their training.

This is a delusion, and a delusion which continues to cast a shadow over the lives of many smart, motivated, and driven young people, many of whom may well end up leaving academia not with a sense of excitement, but a sense of disillusionment.

Nothing could be farther from the reality – they are going where they are more needed, where they will be more welcomed, and where they will have a more tangible impact.

As scientists we dream of having a real-world impact but for academics, their most tangible impact is staring at us in lectures, in practical classes, and in lab meetings. The papers are not the product – the people are.

This reminds me of a tremendous book by Mariana Mazzucato “The Entrepreneurial State”.

In it, she chronicles how scientific investment by governments produces unmatched innovation compared to the private sector — Public investments can take on bigger, and longer term risks (decades), into areas that may not produce immediate commercial value. All of which the private sector is unwilling (or unable to do). And there are tremendous postivie externalities generated through this investment: know how, IP, products and a highly competitive workforce to name a few.

It took me way too long to find this book and thus to better understand where basic scientific research and the markets meet. Highly recommend.

LikeLike

Oh wow, thanks – that’s going straight onto the reading list! There’s another posting I’ve been incubating for a while which is based around asking which aspects of science (research, education, training, drug development etc) are better handled by the public or private sectors respectively. It’s a really interesting question.

LikeLike

I applaud the notion. The challenge, of course, is that – in a world where resources are (understandably and correctly) limited and competitively obtained – the “pursuit of knowledge” or, to rephrase, “the ongoing training of scientific minds”, is not a boundless or necessarily positive investment.

For example, I still regard myself as a scientist (having 4 A-levels in sciences and studied Engineering at university), and am still scientific in my views and approach, although I haven’t actually practiced “science” in any direct way for 20 years (despite having been extremely senior in two of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies)…

So I think I both agree and disagree (a true scientist’s perspective, haha??) – the pursuit of scientific research is valuable, both on a scientific and human level… but only if the quality of the research / scientist is a worthy investment…

Surely, as with most fields, there will be those who are genuinely pushing themselves and their findings forward, and those who simply languish in the funding without really sdtretching themselves or their research?

The scientific question is, presumably, how to measure the difference?

LikeLike

All super-interesting points. Two things I’m now convinced of (to soapbox ranting levels) are that (1) “science” is much more than just academia, and therefore – as you note – scientists are much more widely distributed than universities and research institutes; (2) we can only benefit from training as many PhDs as possible and trying to raise the general level of science literacy in society. The difficulty at the moment is that we are training too many PhDs to fill/replace existing positions in academia but the routes and careers out are not clearly enough signposted.

Obtaining research funding is already extremely competitive, and another interesting question is whether there should be a more equitable distribution of the funds – from an investment angle, the yield tapers off above a certain point, but lavishly funded groups can mask inefficiency of output through volume. By all measures though, fundamental research is something that’s felt to be essential by all scientists but which is perhaps hard to justify when one considers the output in terms of papers…hence the suggested change in optics here.

LikeLike

Nicely said. A few things come to mind. 1. There is a twitter account that you might like/enjoy/hate/whatever named @FromPhDtoLife (Jennifer Polk), that is probably worth checking out (for all I know you already follow her). She is based in Toronto and has a PhD from the University of Toronto (#samesies), but in History. Some lively debate/discussion anyway.

2. These will sound like tired overused platitudes (as opposed to those fresh ones bursting out onto the scene), but “There is no shortage of good ideas” (which I interpret to mean one must be as selective as possible before devoting resources, notice that I do not practice what I preach here), AND, “You will ALWAYS be able to find some highly educated, erudite, opinionated, colleague/friend/acquaintance/nemesis to shoot down your most recent good idea/paper/grant.”

3. The Summer I opened up my very own lab, and hung up my shingle saying “Dr. Marc D. Perry, Developmental Geneticist” I went back to the heartland, Southern Indiana, where both my parents were born (and where I was apparently conceived, hope that is not TMI), where there was a regional C. elegans meeting that year. Over dinner with my Aunt & Uncle, my Cousins, and my Cousin’s kids I explained how I was being funded (yes, that is right, with taxpayer dollars) to work on tiny, practically “invisible” worms, and (wait for it) we were studying their “sex” (well, sex determination if the truth be told, but to the lay public just saying sex at the dinner table like that could make someone’s beverage spray from their nose, they were laughing so hard). Oh my gosh, I tell ya, there is some crazy stuff going on over at those universities these days. Y’all have no idea . . .

NEW TOPIC:

I despaired at the idea that this blog might end after you shut down your lab and switched employers, so I am very glad to see that you are continuing to write and post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Marc! Thanks for the tip – Twitter account now being followed.

The blog is definitely not going to end (writing is too much of a compulsion), but it’s possible that the focus may shift a bit once I’ve left academia and started in the private sector. I’m sure that in itself will be a fertile source of comparative postings anyway though, so TIR is going nowhere just yet! 🙂

LikeLike

Fantastic post, as usual, Brooke. I could not agree more – I may have written something about it too, back when I was a PhD student and activist in Spain, in a letter to a politician.

It is depressing to think of the neglect that young scientists endure, sometimes even when PIs do try their best (I have been an independent scientist now for 10 years, had 3 PhD students, and none of them have papers of their own yet).

I think that a big part of the problem is that PIs are rewarded by this training only very indirectly and long-term. It is obvious that having a successful scientific offspring is helpful, but only if they themselves become successful academics. This takes a long while, and may not necessarily depend, ahem, on good scientific training.

Meanwhile, Departments have yearly targets of PhD graduates (in the UK, at least), but whatever happens with them later on is irrelevant.

I have always thought that the only way to shake things up would be through new metrics: having University rankings depend also on how many research graduates have a job with a salary commensurate with their qualification 6mo/1y after graduating. Just as it happens with bachelor graduates. That may tip the scales a bit so Departments give proper brownie points to PIs who do a good job with their students, regardless(*) of the science their students contribute to.

(*) Regardless to a point – it is difficult to train a researcher properly if they are not capable of doing good research!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Joaquin, huge thanks as always for taking the time to write. I agree completely that there is simply not enough incentive to make group leaders invest in training PhDs – unfortunately, I suspect it’s often more critical obtaining the money that comes with the PhD rather than caring overmuch about the fate of the person who takes that position. This is a bad thing. I think your point about having successful offspring only being a long-term benefit is spot on, and this is something that hadn’t occurred to me before (thanks!).

I agree too that there need to be (spoiler: future posting!) structural changes to make group leaders/departments think more about the outcomes for students in their care than at present.

LikeLike